Inzululwazi

Inzululwazi iyisigabavu esihleliwe nendlela yokuzuza lonke ulwazi olungaba khona emhlabeni nakumkhathilibe wonke. Kwinzululwazi kukhona izindlela zokuhlela izincazelo ezivivinyayo nokubikezela ngomkhathi. [1] [2] Kubalulekile kakhulu kwinzululwazi ukuba imiphumela yezivivinyo nocwaningo kube eqinisekiswe osonzululwazi abaningi ukuze amaqiniso ayo angaphuma odwa kuvezwa amaphutha. Kwencikene kakhulu nokusizana kuhlanganwe.

Izimpande zokuqala zenzululwazi ziseGibhithe lasendulo naseMesopotamiya kusukela cishe ngowezi-3500 kuya ku-3000 BCE.[3] [4] Amagalelo abo kwezomchazazibalo, ezomchazamkhathi, kanye nezokwelapha angena futhi abumba iFilosofi yemvelo yamaGreki yenkathi yakudala, okuyilapho kwenziwa khona imizamo emisiwe yokuqhamuka nezincazelo ezisekelwe emsukeni ongokwemvelo wezinto ezenzeka endaweni ebonwa ngamehlo. Ngemuva kokuwa koMbuso oseNtshonalanga WaseRoma, ulwazi lwemiqondo yamaGrikhi ngomhlaba lwehla eNtshonalanga Yurophu phakathi neminyaka engamakhulu amane yokuqala (eyama-400 kuya kwe-1000 CE) weNkathi Ephakathi [5] kepha lwalondolozwa emazweni obuSulumane ngesikhathi se- nkathi yokuChuma kobuSulumane. [6] Ukubuyiselwa nokuhlanganiswa kwemisebenzi yamaGrikhi nemibuzo yamaSulumane eNtshonalanga Yurophu kusuka ngekhulu le-10 kuye le-13 kwavuselela "iFilosofi yemvelo", [7] kamuva eyaguqulwa yinguquko yenzululwazi eyaqala ngekhulu le-16 [8] njengoba amasu amasha kanye nokusanda-kufunyanwa kwayishiya imiqondo namasiko wamaGrikhi kwangaphambili. [9] [10] [11] [12] Indlela-su yenzululwazi ngokushesha yadlala indima enkulu ekwakhiweni kolwazi futhi kuze kwaba ngekhulu lam-19 lapho izici eziningi zezikhungo nokucwephesha zenzululwazi ezaqala ukwakheka; [13] [14] [15] kanye nokushintshwa "kwefilosofi yemvelo" kube isayensi yemvelo. [16]

Inzululwazi yanamuhla ngokuvamile ihlukaniswe yaba amagatsha amathathu amakhulu aqukethe inzululwazi yemvelo (isib, umchazampilo, umchazatho, kanye nomchazandalo), efunda imvelo ngomqondo obanzi; inzululwazi yezenhlalo (isib, Ezomnotho, ezengqondo, kanye nezenhlalo), ezifunda abantu ngabanye nemiphakathi; kanye nesayensi ehlelekile (isib. umhluzaqondo, umchazazibalo, kanye nesayensi yesiCikizi semibhalo), ephathelene nezimpawu ezilawulwa yimithetho. Kodwa kukhona ukungaboni ngaso linye, [17] [18] ekutheni inzululwazi ehlelekile empeleni yakha inzululwazi njengoba ingasekelwe ebufakazini obungcwetile. [19] Imikhakha esebenzisa ulwazi olukhona lwenzululwazi ngezinjongo ezisebenzayo, enjengomNgcikisho, ezokwelapha, zichazwa njengenzululwazi esetshenziswayo. [20] [21] [22] [23]

Ulwazi olusha lwenzululwazi luthuthukiswa ucwaningo losonzululwazi abagqugquzelwa ilukuluku ngokuphathelene nomhlaba kanye nayisifiso sokuxazulula izinkinga. Ucwaningo lwenzululwazi lwanamuhla lwenziwa ngokubambisana okukhulu futhi luvame ukuqhutshwa amathimba akwezemfundo, izikhungo zokucwaninga, izikhungo zikahulumeni nezinkampani. Umthelela osebenzayo ocwaningweni lwenzululwazi uholele ekuqubukeni kwezinqubomgomo zesayensi ezifuna ukuthonya umhwebo wenzulukeazi ngokubeka phambili ukuthuthukiswa kwemikhiqizo yezentengiso, izikhali, ukunakekela impilo, futhiukuvikelwa kwemvelo.

uMsuka

[hlela | Hlela umthombo]Igama elithi inzululwazi elisetshenziswa ukuhumusha elithi science lisho 'isimo sokwazi', noma ulwazi olunzulu ngendalo ezungezile. Igama elithi inzululwazi liyinhlanganisela yamabizo amabili athi 'nzulu + ulwazi' ngoba loluhlobo lolwazi lunzulu, ludinga ukufundwa kabanzi nokucwaningwa ngokujulile. Lingcono kakhulu kunalelo elingumfakela othi isayensi. Leli liyibizo lesintu okufanele silisebenzise. Nansi indlela yokulisebenzisa lona kanye namanye ahlobene nalo:

- science - inzululwazi

- scientist - usonzululwazi

- scientific - okwenzululwazi

.

uMlando

[hlela | Hlela umthombo]uMlando wakuqala

[hlela | Hlela umthombo]

Inzululwazi ayinawo umsuka owodwa vo. Kunalokho, izindlelasu ezihleliwe zavela lusilili ngokuhamba kwesikhathi seminyaka engaphezu kwezinkulungwane,[24][25] ngezimo ezingafani ezingxenyeni ezihlukene zomhlaba, futhi inbalwa imininingwane ekhona emayelana nokuthuthuka kwayo endulo. Kungenzeka abesifazane babeneqhaza elikhulu kwinzululwazi yasendulo,[26] as did religious rituals.[27] Ezinye izazi zisebenzisa ebizo elithi 'inzululwazi yanguna' ukuze bagqabe ubuqhebeqhebe basendulo obunenswebu yenzululwazi yanamuhla kulwangu lwayo;[28][29][30] nokho, lomgqabo uye wahlatshwa kakhulu njengothunazayo[31] noma osikisela ngokweqile umbono wobumanjemanje (Presentism), njengoba ubhekwa Lobo buqhebeqhebe ngeso lemijinjo yanamuhla.[32]

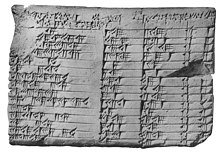

Ubufakazi obuqandikhanda bemidludlungu yenzululwazi baqala ukucaca ekufikeni kwezimiso zokubhala emiphakathini yasendulo njengaseGibhithe naseMesopothamiya, kanjalo kwaqopheka iziqoshwa zokuqala emlandweni wenzululwazi.[33][4] Nakuba amazwi nezicabangelo ezithi 'inzululwazi' nesithi 'imvelo' zazingeyona ingxenye yenkulumo yangaleso sikhathi, imiphakathi yasendulo yaba namagalelo abalulekile naba nendawo kwinzululwazi yamaGrikhi nasenkathini ephakathi.

Abantu baseMesopothamiya lasendulo basebenzisa ulwazi olumalungana nezakhi ezihlukene zeziqa ukuze bakhiqize amakhamba, izindindimana, inhlaka, insipho, izinkimbi, isinomfiya, nesivimbamanzi.[34] Bacwaninga uchazomzimba lwezilwane, ukucondoza kwezilwane, nomchazanyezi ngezinjongo zokubhula.[35] AbaseMesopothamiya babenentshiseko enkulu kwezokwelapha[34] futhi iziyalo zemitho zokuqala zavela ngolimi lwamakhaledi ngoSendo lwesithathu lwase-Uri.[36] Babegxile kakhulu ekufundeni izihloko zenzululwazi ezazisebenziseka kwezenkolo nasempilweni futhi babengakuthakaseli ukugculisa ilukuluku.[34]

Enkathini yanguna

[hlela | Hlela umthombo]

Enkathini yanguna, babekhona ababebhekwa njengosonzululwazi, kodwana hhayi ngendlela efana neyanamuhla. Abantu abayizinyanga ezigogodile, nabayingxenye yezicukuthwane futhi imvama abesilisa yibona ababeqhogoya izinhlobonhlobo zophenyo emvelweni.[37]

Enkathini ephakathi

[hlela | Hlela umthombo]

Ngenxa yokuwa kombuso waseRoma, ikhulu lesi-5 lambozwa ukwehla kwezingqithabuchopho nokuwohloka kolwazi olwalukhona endulo.[33]Template:R/superscript

Enkathini yokukhanyiselwa

[hlela | Hlela umthombo]

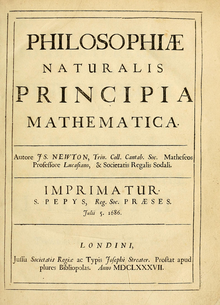

Ekuqaleni kwenkathi yokukhanyiselwa, uIsaac Newton wakha isisekelo sobunguxa basendulo ngencwadi ethi Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, eyaba nethonya elikhulu kwezomchazandalo.[38] U-Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz wasebenzisa amabizo womchazandalo wobu-Aristotile, okuyiwona asetshenziswa ngendlela entsha.

Izinkomba

[hlela | Hlela umthombo]- ↑ Wilson, E.O. Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge.

- ↑ "... modern science is a discovery as well as an invention. It was a discovery that nature generally acts regularly enough to be described by laws and even by mathematics; and required invention to devise the techniques, abstractions, apparatus, and organization for exhibiting the regularities and securing their law-like descriptions."— p.vii Heilbron, J.L. (editor-in-chief). The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science.

- ↑ "The historian ... requires a very broad definition of "science" – one that ... will help us to understand the modern scientific enterprise. We need to be broad and inclusive, rather than narrow and exclusive ... and we should expect that the farther back we go [in time] the broader we will need to be." p.3—Lindberg, David C. (2007). "Science before the Greeks". The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (Second ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 1–27. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Grant, Edward (2007). "Ancient Egypt to Plato". A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century (First ed.). New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-052-1-68957-1.

- ↑ Lindberg, David C. (2007). "The revival of learning in the West". The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (Second ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 193–224. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ↑ Lindberg, David C. (2007). "Islamic science". The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (Second ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 163–92. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ↑ Lindberg, David C. (2007). "The recovery and assimilation of Greek and Islamic science". The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (2nd ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 225–53. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ↑ Principe, Lawrence M. (2011). "Introduction". Scientific Revolution: A Very Short Introduction (First ed.). New York, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-199-56741-6.

- ↑ Lindberg, David C. (1990). "Conceptions of the Scientific Revolution from Baker to Butterfield: A preliminary sketch". Reappraisals of the Scientific Revolution (First ed.). Chicago, Illinois: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-0-521-34262-9.

- ↑ Lindberg, David C. (2007). "The legacy of ancient and medieval science". The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (2nd ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 357–368. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ↑ Del Soldato, Eva. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2016 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ↑ Grant, Edward (2007). "Transformation of medieval natural philosophy from the early period modern period to the end of the nineteenth century". A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century (First ed.). New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 274–322. ISBN 978-052-1-68957-1.

- ↑ From Natural Philosophy to the Sciences: Writing the History of Nineteenth-Century Science. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-08928-7.

- ↑ The Oxford English Dictionary dates the origin of the word "scientist" to 1834.

- ↑ Lightman, Bernard. "13. Science and the Public". Wrestling with Nature : From Omens to Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226317830.

- ↑ Harrison, Peter. The Territories of Science and Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 164–165. ISBN 9780226184517.

- ↑ Bishop, Alan (1991). "Environmental activities and mathematical culture". Mathematical Enculturation: A Cultural Perspective on Mathematics Education. Norwell, Massachusetts: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 20–59. ISBN 978-0-792-31270-3.

- ↑ Bunge, Mario. "The Scientific Approach". Philosophy of Science: Volume 1, From Problem to Theory. New York, New York: Routledge. pp. 3–50. ISBN 978-0-765-80413-6.

- ↑ Fetzer, James H. (2013). "Computer reliability and public policy: Limits of knowledge of computer-based systems". Computers and Cognition: Why Minds are not Machines. Newcastle, United Kingdom: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 271–308. ISBN 978-1-443-81946-6.

- ↑ Fischer, M.R. (2014). Thinking and acting scientifically: Indispensable basis of medical education. pp. Doc24.

- ↑ Abraham, Reem Rachel (2004). Clinically oriented physiology teaching: strategy for developing critical-thinking skills in undergraduate medical students. pp. 102–04.

- ↑ Sinclair, Marius. On the Differences between the Engineering and Scientific Methods.

- ↑ "Engineering Technology :: Engineering Technology :: Purdue School of Engineering and Technology, IUPUI". Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ↑ Carruthers, Peter (2002-05-02), Carruthers, Peter; Stich, Stephen; Siegal, Michael, eds., "The roots of scientific reasoning: infancy, modularity and the art of tracking", The Cognitive Basis of Science (Cambridge University Press): pp. 73–96, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511613517.005, ISBN 978-0-521-81229-0

- ↑ Lombard, Marlize; Gärdenfors, Peter (2017). "Tracking the Evolution of Causal Cognition in Humans". Journal of Anthropological Sciences 95 (95): 219–234. doi:10.4436/JASS.95006. ISSN 1827-4765. PMID 28489015.

- ↑ Graeber, David; Wengrow, David (2021). The Dawn of Everything. p. 248.

- ↑ Budd, Paul; Taylor, Timothy (1995). "The Faerie Smith Meets the Bronze Industry: Magic Versus Science in the Interpretation of Prehistoric Metal-Making". World Archaeology 27 (1): 133–143. doi:10.1080/00438243.1995.9980297. JSTOR 124782.

- ↑ Tuomela, Raimo (1987). "Science, Protoscience, and Pseudoscience". In Pitt, J.C.; Pera, M. Rational Changes in Science. Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science. 98. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 83–101. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-3779-6_4. ISBN 978-94-010-8181-8.

- ↑ Smith, Pamela H. (2009). "Science on the Move: Recent Trends in the History of Early Modern Science". Renaissance Quarterly 62 (2): 345–375. doi:10.1086/599864. PMID 19750597.

- ↑ Fleck, Robert (March 2021). "Fundamental Themes in Physics from the History of Art" (in en). Physics in Perspective 23 (1): 25–48. Bibcode 2021PhP....23...25F. doi:10.1007/s00016-020-00269-7. ISSN 1422-6944. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00016-020-00269-7.

- ↑ Scott, Colin (2011). "Science for the West, Myth for the Rest?". In Harding, Sandra. The Postcolonial Science and Technology Studies Reader. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 175. doi:10.2307/j.ctv11g96cc.16. ISBN 978-0-8223-4936-5. OCLC 700406626.

- ↑ Dear, Peter (2012). "Historiography of Not-So-Recent Science". History of Science 50 (2): 197–211. doi:10.1177/007327531205000203.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedLindberg2007a - ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 McIntosh, Jane R. (2005). Ancient Mesopotamia: New Perspectives. Santa Barbara, California, Denver, Colorado, and Oxford, England: ABC-CLIO. pp. 273–76. ISBN 978-1-57607-966-9. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Kulandwe ngomhlaka October 20, 2020. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Aaboe, Asger (May 2, 1974). "Scientific Astronomy in Antiquity". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 276 (1257): 21–42. Bibcode 1974RSPTA.276...21A. doi:10.1098/rsta.1974.0007. JSTOR 74272.

- ↑ Biggs, R D. (2005). "Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health in Ancient Mesopotamia". Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies 19 (1): 7–18.

- ↑ Lehoux, Daryn (2011). "2. Natural Knowledge in the Classical World". In Shank, Michael; Numbers, Ronald; Harrison, Peter. Wrestling with Nature: From Omens to Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-226-31783-0.

- ↑ Gribbin, John (2002). Science: A History 1543–2001. Allen Lane. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-7139-9503-9.

Although it was just one of the many factors in the Enlightenment, the success of Newtonian physics in providing a mathematical description of an ordered world clearly played a big part in the flowering of this movement in the eighteenth century

Izixhumanisi ezingaphandle

[hlela | Hlela umthombo]- Euroscience Archived 2010-04-12 at the Wayback Machine.

- Classification of the Sciences in Dictionary of the History of Ideas. (Isimo esisha se-elekthronikhi sinobhomu kabi, okufakiwe ngemuva kokuthi "Idizayini" ingafinyeleleki. Internet Archive inguqulo yakudala).

- United States Science Initiative Imininingwane ekhethiwe yesayensi enikezwe izinhlaka zikaHulumeni wase-US, kufaka phakathi ucwaningo nemiphumela yokuthuthuka

- How science works University of California Museum of Paleontology